How Do You Reason?

Reason differently with these methods that can help you think better

I thought that there was only one kind of reasoning, and that was logical reasoning. However, my understanding of reasoning changed when I read Being You: A New Science of Consciousness by Anil Seth (ISBN 978 0 571 3372 9).

In his book, Anil Seth describes three different types of reasoning:

Deductive

Inductive

Abductive (Bayesian)

Deductive Reasoning

Deductive reasoning is one of the most common forms of reasoning. It is a logical process in which a conclusion is guaranteed to be true if the premises are true. It moves from general principles to a specific conclusion.

Deductive reasoning is used in maths, science, programming, formal arguments and philosophy.

Example

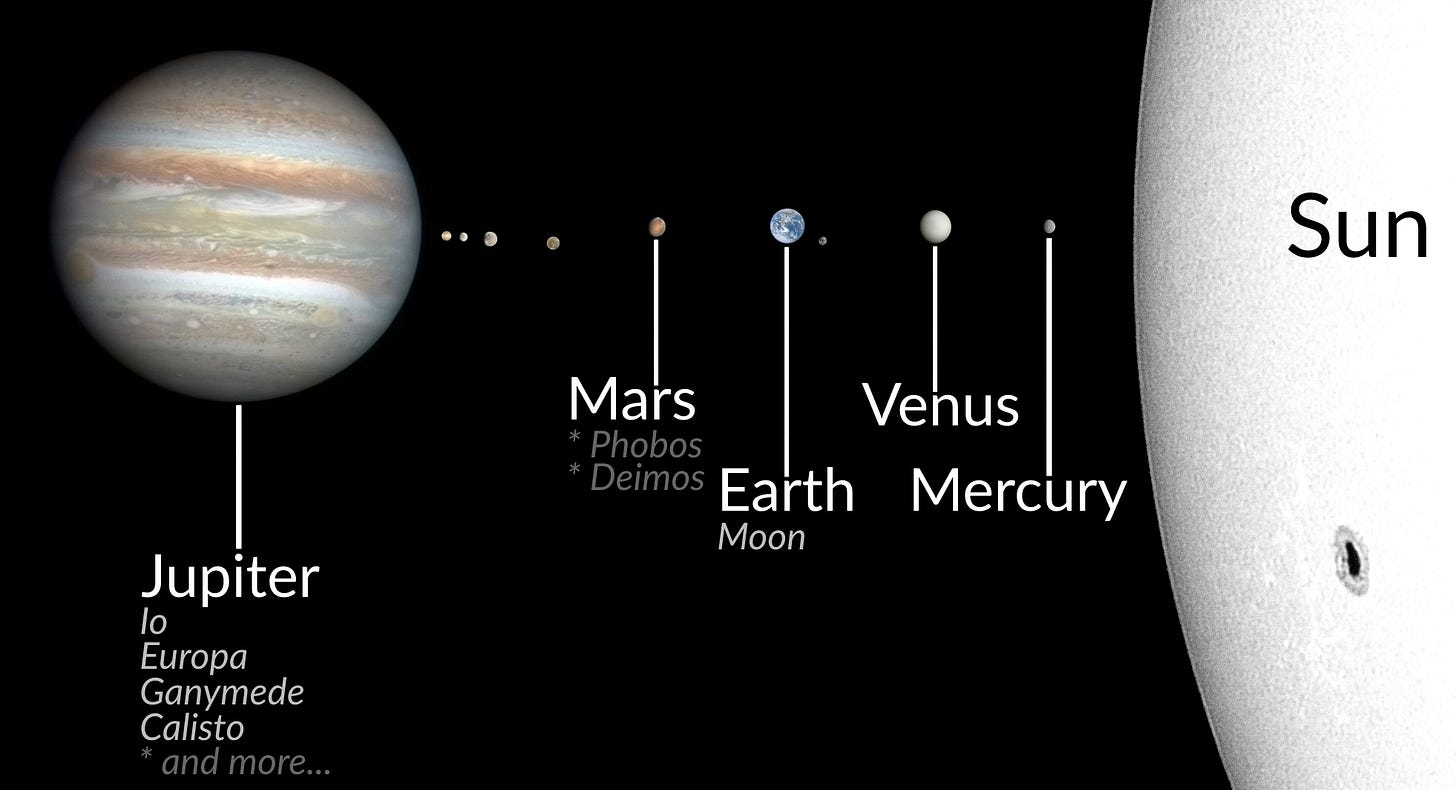

If Venus is closer to the Sun than the Earth, and the Earth is closer to the Sun than Mars, then Venus is closer to the Sun than Mars.

Inductive Reasoning

Inductive reasoning is a type of logical thinking that involves making generalisations based on specific observations or examples. Unlike deductive reasoning, inductive reasoning does not guarantee the conclusion, but suggests that the conclusion is probably true.

Inductive reasoning is used in:

Science: forming hypotheses based on experiments

Everyday life: “My last three trains were late → trains are often late.”

Journalism and history: spotting trends from evidence.

Example

The sun has risen in the east every day of my life.

Therefore, the sun always rises in the east.

The conclusion is highly likely, but not guaranteed. It’s based on repeated observations, not on strict logical proof.

Abductive or Bayesian Reasoning

Abductive or Bayesian reasoning is about reasoning with probabilities. It is a form of logical inference that begins with an incomplete set of observations and looks for the most likely explanation. It’s often described as ‘inference to the best explanation’.

Like inductive reasoning, Bayesian reasoning can also come to the wrong conclusion. It is often used when speed or practicality is more important than formal proof.

Example

Observation

The grass is wet this morning.Possibilities

It’s wet because it rained last night, someone watered the lawn, or there was dew.Conclusion

It probably rained last night.

You’re picking the most plausible explanation, even though it’s not the only possible one.

Bayesian reasoning is used in:

Medicine: A doctor sees symptoms and chooses the most likely diagnosis.

Crime investigation: A detective infers the most likely cause of a crime.

Science: Hypothesis formation based on puzzling data.

Reverend Thomas Bayes

The Reverend Thomas Bayes (1702-1761) was a Presbyterian minister, philosopher, and statistician who lived much of his life in Tunbridge Wells, southern England, but never published the theorem that immortalised his name.

His ‘Essay Towards Solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances’ was presented to the Royal Society in London two years after his death by fellow preacher-philosopher Richard Price, and much of the mathematics was done later by the French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace.

But it is Bayes whose name is forever tied to a way of reasoning called ‘inference to the best explanation’, the insights from which are central to understanding how conscious perceptions are built from brain-based best guesses.

Conclusion

Deductive, inductive, and abductive (Bayesian) reasoning each offer a distinct way of making sense of the world. Deduction gives us certainty when our premises are sound, induction allows us to learn from patterns and experience, and abductive reasoning helps us act intelligently in the face of uncertainty by weighing the most plausible explanations.

In practice, effective thinking rarely relies on just one of these forms. We move fluidly between them: forming hypotheses abductively, testing them inductively, and applying conclusions deductively. Understanding the strengths and limits of each type of reasoning not only sharpens our judgment but also makes us more aware of how we think—and why some conclusions feel compelling while others deserve caution.

By recognising when to seek certainty, when to accept probability, and when to infer the best explanation, we can reason more clearly, make better decisions, and respond more thoughtfully to the complexity of real-world problems.